On a bright, cold morning in December 1928, the Swedish ocean liner M/S Kungsholm glided into New York Harbour for the first time. Steam rose from the decks, gulls wheeled overhead, and crowds gathered at the piers. They had read the rumours: the ship approaching Manhattan was said to be unlike anything that had crossed the Atlantic before.

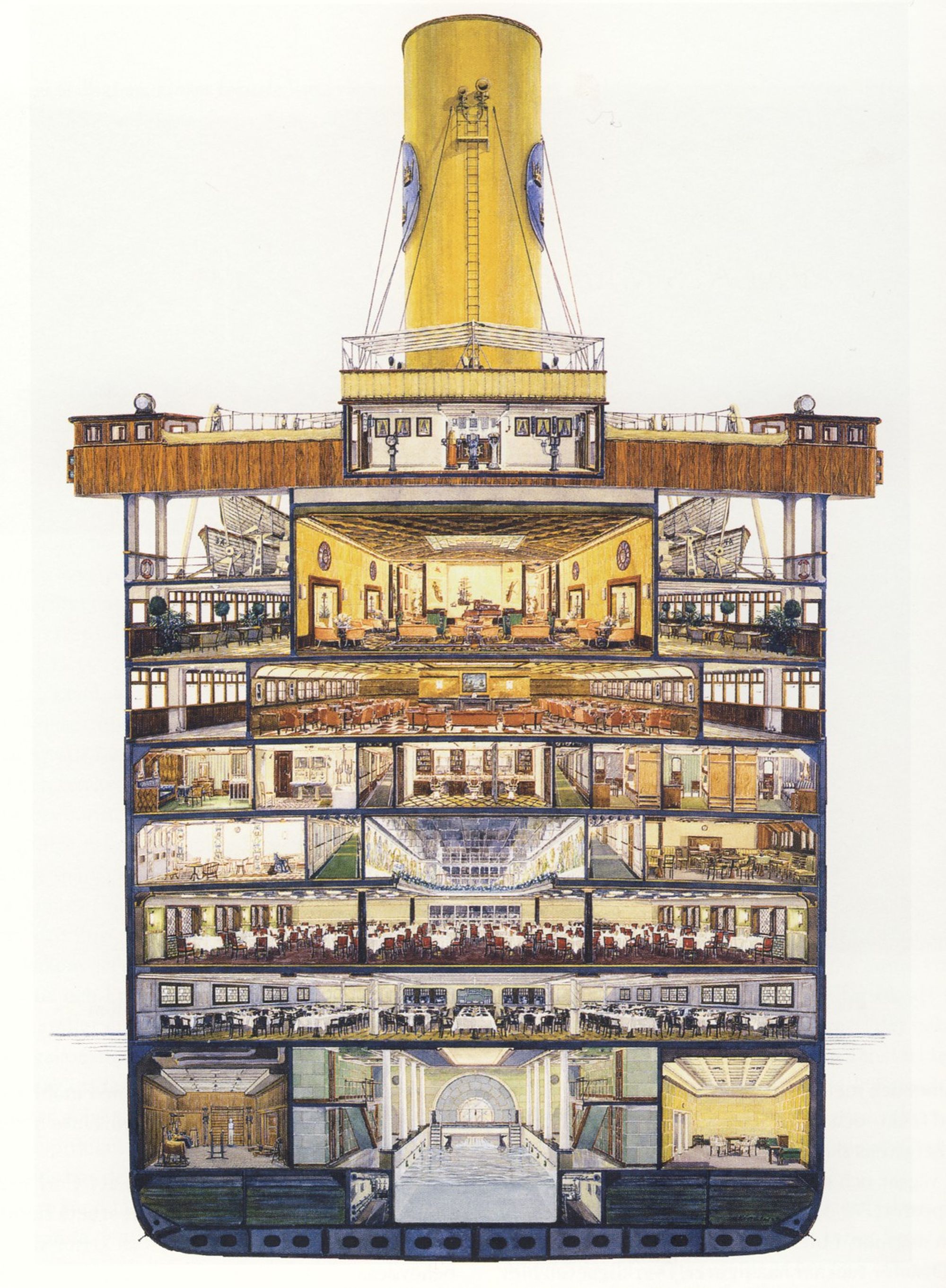

Beneath her sober black hull and pale superstructure, Kungsholm concealed an extraordinary secret — a world-class showcase of Swedish design. Newspapers would soon call it a “floating palace”, and with reason: every cabin, lounge and corridor had been created to demonstrate the skill and imagination of Sweden’s leading designers at a moment when the world was discovering Scandinavian craftsmanship.

M/S Kungsholm was a floating masterpiece, displaying the pinnacle of Swedish craftsmanship in the age of Swedish Grace. © Public Domain

A Floating Masterpiece

The Swedish American Line commissioned the architect Carl Bergsten, celebrated for Sweden’s pavilion at the 1925 Paris Exposition, to design the ship’s interiors. His task was bold: to present Swedish decorative arts on an international stage, not in a museum, but at sea.

He gathered a remarkable team, including Carl Malmsten, Märta Måås-Fjetterström, Anna Petrus, Edward Hald, Simon Gate, Elsa Gullberg. Together they created one of the most ambitious Scandinavian interiors ever attempted: a serene, geometric, light-filled interpretation of the era we now call Swedish Grace, the Nordic sibling of art deco.

Guests encountered rooms lined in Javanese teak and grey-stained oak, patterned parquet floors, sculptural lighting and textiles woven specifically for the ship. The result was not simply decoration; it was a a total work of art gliding across the North Atlantic.

© Public Domain

Mirror Mirror on the Wall

Among the artists invited aboard was Gunnar Ström, a painter known for his decorative work in churches and public buildings. His contribution to the ship was a series of mirror paintings designed for the second-class smoking lounge — an elegant room with a vaulted glass ceiling, a bar, and clusters of upholstered chairs arranged beneath the soft haze of tobacco smoke.

Between the windows hung Ström’s works: Swedish lighthouses, each painted onto partially silvered mirror glass and framed in red and gold chinoiserie-style surrounds. They were both paintings and reflections — artworks that subtly shifted as passengers moved through the room.

One of these, depicting the rugged Bohuslän landscape and the famous Pater Noster Lighthouse, seemed almost to glow from within. Fishermen haul nets in the foreground; the beacon stands resolute behind them. Seen against the backdrop of teak and brass, the effect must have been mesmerising.

A Golden Age, Undone by War

For just over a decade, Kungsholm carried travellers between Europe, North America and the Caribbean, earning a reputation for elegance and comfort. But the outbreak of the Second World War changed everything.

In 1942, the United States requisitioned the ship, renamed her John Ericsson, and converted her for use as a troop transport. The overhaul was swift and devastating.

Valuable wood panels were nailed through, gilded leather wall coverings torn down, bespoke furnishings thrown onto the docks. Entire rooms were gutted in days.

Once called “a fairy-tale castle at sea”, the ship has left only a few traces behind for future generations.

What had once been one of the finest Swedish interiors ever created was reduced almost instantly to scrap.Only fragments survived.

Rescued in a Suitcase

One of the few Swedes who remained on board during the conversion was Gösta Sjögren, the ship’s third officer. As the interiors were stripped, Sjögren decided to rescue at least one piece of the ship’s past. He removed the Pater Noster mirror from the smoking lounge, wrapped it carefully, and placed it in his suitcase.

It was, in part, a gesture of affection: Sjögren was himself from Bohuslän, the region depicted in the painting.

)

First Officer Gösta Sjögren rescued the mirror from demolition by slipping it into his suitcase as he left the ship. He is said to have been particularly fond of its coastal scene, reminding him of home.

The mirror travelled with him back to Sweden after the war. It remained in his family for decades, quietly preserved, never publicly exhibited, a private relic of a vanished world.

Today, almost a century after the ship’s maiden voyage, the mirror returns to the public through Stockholms Auktionsverk.

Surviving Fragments of Swedish Grace

Measuring 64 × 58.5 cm, the mirror is a rare survivor from one of Sweden’s most important design projects. Its partially silvered surface, polychrome painting and ornate red frame capture the spirit of the late 1920s, a moment when Swedish design balanced classicism with modernity, craftsmanship with innovation.

Almost all of Kungsholm’s original interiors were destroyed or dispersed. A few pieces have surfaced on the market over the years, but the vast majority are lost forever.

This is what gives Ström’s Pater Noster its extraordinary resonance. It is more than an artwork. It is a portal — a glimpse into a ship that once carried the very best of Swedish artistry across the Atlantic.

Echoes of a Lost Era

M/S Kungsholm has been described as “a masterpiece of Swedish Art Deco”, and today only scattered fragments remain. Yet even in isolation these fragments speak clearly. They remind us of a moment when design, craftsmanship and seafaring converged into something dreamlike, a total work of art afloat.

As Ström’s mirror appears in The Modern Art & Design Sale, it offers more than historical interest. It offers a journey back to 1928, to the era when Sweden took its place on the world’s design stage.

)

)