In March 1905, a handful of Cambridge‐educated friends began gathering every Thursday night in a modest Gordon Square townhouse in Bloomsbury. They debated Post-Impressionism, pacifism and free love beneath flickering gas lamps, scandalising Edwardian society.

Within a decade those conversations – led by writers Virginia Woolf and Lytton Strachey, painter Vanessa Bell and economist John Maynard Keynes – had birthed the Bloomsbury Group, a loose collective that rejected Victorian moral codes and championed modern art. Their bohemian ideals still colour literature, interior design and, crucially, the auction market – where a Bell textile or Duncan Grant canvas now commands spirited bidding.

Typical Bloomsbury aesthetics. Interior snapshots from Charelston Farmhouse. Photo: Lee Robbins © Courtesy of: Charleston Trust

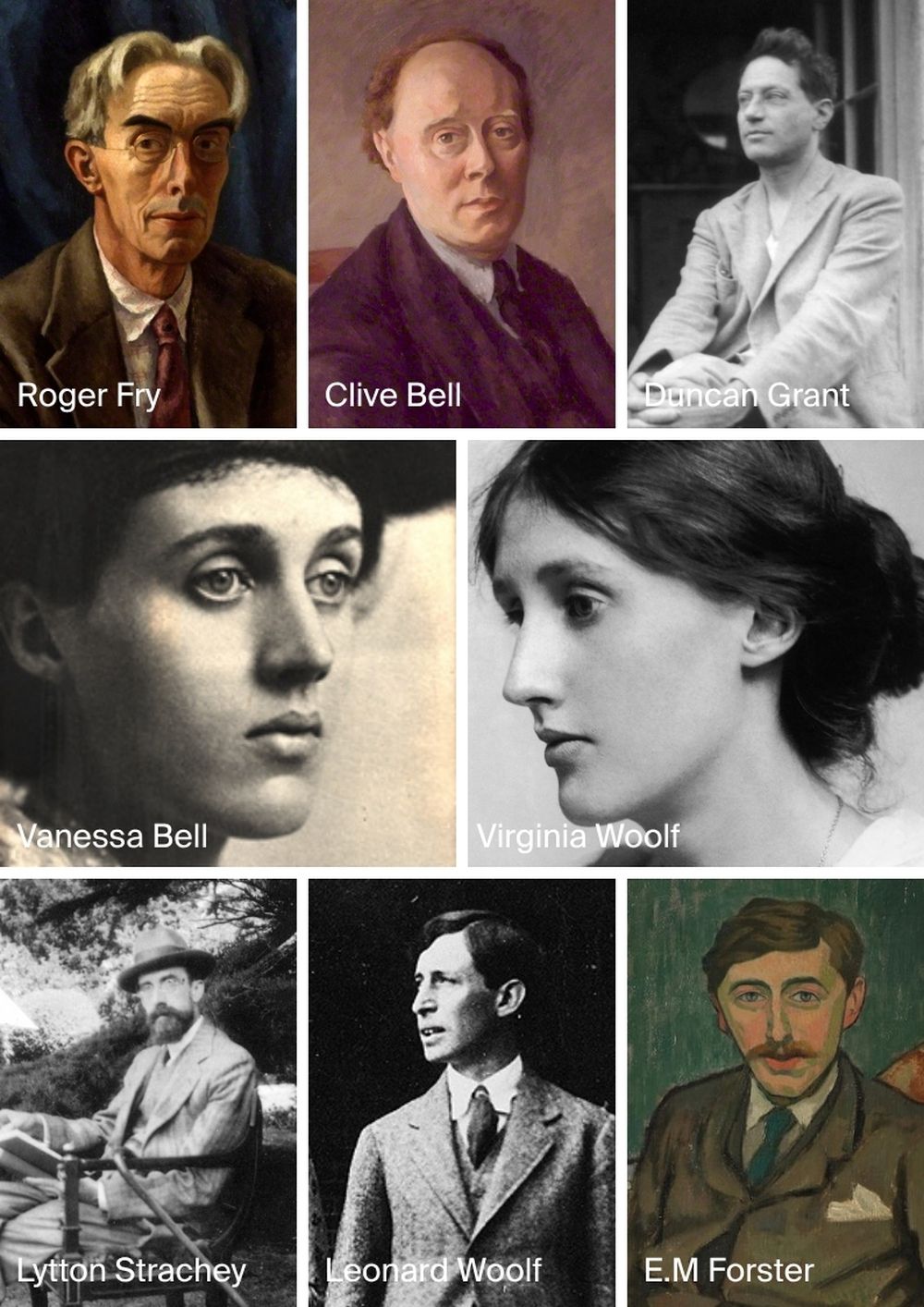

Who Sat Around the Bloomsbury Table?

The core circle included three Clapham siblings – Virginia, Vanessa and Adrian Stephen – plus university friends Clive Bell, Duncan Grant and Lytton Strachey. Soon the circle widened to welcome critic Roger Fry, biographer (and later gardener-designer) Vita Sackville-West, Victorian-satire pioneer E.M. Forster, and political firebrand Keynes.

Some of the original Bloomsbury members. Collage: Images from Charleston Trust and Wikimedia Commons

While not a formal “movement,” the group shared a belief that personal relationships and aesthetic experience mattered more than public duty – radical thinking in Edwardian England. Their gatherings blurred disciplines: a Fry lecture on Cézanne might segue into a Keynes riff on free-trade theory, followed by Vanessa sketching guests beneath abstract lampshades.

Shaking London’s Art Scene: Post-Impressionism Arrives

Roger Fry’s 1910 exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists exploded like a paint-filled grenade at the Grafton Galleries, shocking audiences with Gauguin’s flats of colour and Cézanne’s fractured perspectives.

Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant joined Fry in founding the short-lived but influential Omega Workshops (1913-19), where artists could design ceramics, furniture and textiles anonymously, signed only with Ω. Their hand-blocked linen, swirling in Fauvist oranges and Prussian blues, outraged traditionalists yet laid foundations for British modern design.

Today a single Omega chair can fetch five figures – proof that Bloomsbury style, once derided as “fauve nursery,” is now prized décor.

Queen of Bohemia. In 1917, Roger Fry painted Nina Hamnett wearing a dress designed by Vanessa Bell and produced at the Omega Workshops. Her shoes may also be from Omega, and the chair’s cushion is covered in ‘Maud’ linen, another design by Bell. © Wikimedia Commons

Charleston: a Living Laboratory of Colour

Unable to enlist during World War I, Grant and Bell decamped to Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, transforming its whitewashed walls into story-book murals: Italianate angels by the hearth, Greek nymphs across cupboard doors. Every surface became a canvas – fireplace surrounds, lampshades, even bedposts.

Charleston turned domesticity into installation art and remains a pilgrimage site. Collectors hunt early Grant nudes or Bell still-lifes for their radical palette. Textiles hand-printed at Charleston, once kitchen curtains, now appear on Auctionet beside Windsor chairs and avant-garde ceramics, a testament to cross-disciplinary appeal.

Interior at Charleston Farmhouse. Photo: Euan Baker © Courtesy of: Charleston Trust

Words that Redrew the Novel – and Social Norms

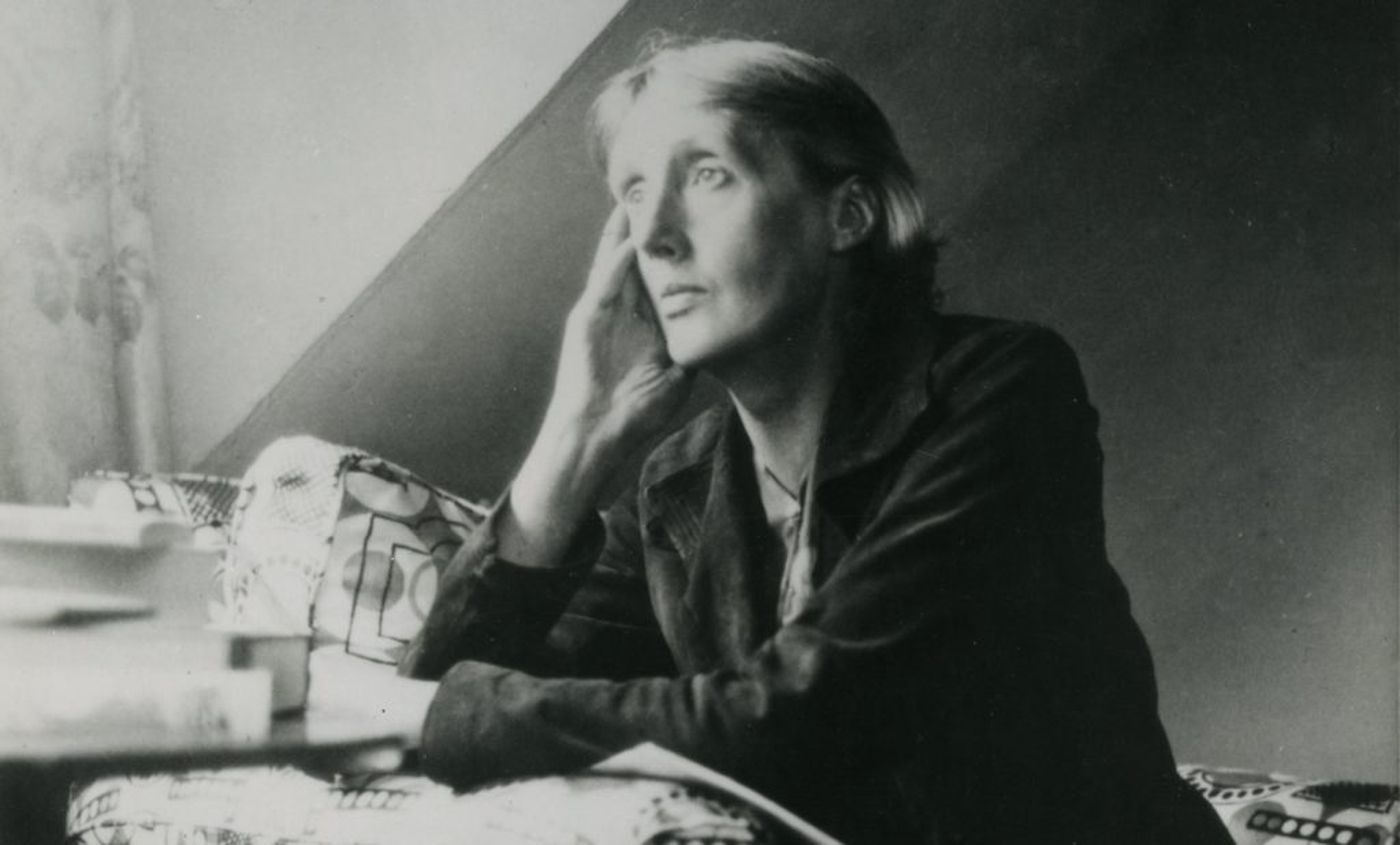

While the painters splashed colour, Bloomsbury’s writers rewired English prose. Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) threaded stream-of-consciousness through a single London day; Strachey’s Eminent Victorians (1918) skewered public‐school hero worship with irony.

Virginia Woold Writing © Charleston Trust

Both books remain syllabus staples, fueling a manuscript market. Letters between group members – revealing polyamorous tangles and pacifist letters to the Times – now appear in catalogues as micro-monuments to early 20th-century social revolution.

Market Momentum: Why Bloomsbury Still Climbs

Scarcity meets story. Many works stayed within families until late 20th-century estate dispersals; each tranche re-energised prices. A niche of textile aficionados now chase Bell’s Omega rugs with fervour usually reserved for Bauhaus lamps – the same collecting psychology Auctionet’s editors observed when charting the surge in design-icon prices from Windsor chairs to Bauhaus desk lamps.

Tips for New Bloomsbury Bidders

Condition counts: Omega pieces were handmade; minor irregularities are a plus, later retouching is not.

Provenance tells the tale: Items traced to Charleston or Monk’s House brochures carry a premium.

Cross-category value: A Fry lithograph may sit cheaper than a Grant oil, but both share the same narrative thread – buy what speaks to you.

Legacy in Today’s Interiors – and on Auctionet’s Carousel

Bloomsbury’s mix-and-match ethos – bold pattern beside Georgian furniture, Greek vases flanking modernist portraits – mirrors how contemporary collectors curate homes and digital auction wish-lists.

Auctionet’s continuous-sale model means you can pair a Bloomsbury side table with Scandinavian minimalism in a single afternoon’s browsing. Set a saved search for “the Bloomsbury Group”, “Omega Workshops", or “Vanessa Bell” and new consignments will ping your inbox faster than Virginia could draft a diary entry.

Conclusion: Rewriting Life and Art – Again

The Bloomsbury Group dismantled barriers between painting, poetry, politics and domestic life, leaving a palette-rich legacy that still brightens galleries and living rooms. As fresh archives emerge and museum retrospectives proliferate, demand for Bloomsbury works continues its steady climb.

Ready to add a dash of Post-Impressionist colour – or an Omega footstool – to your collection? Explore Auctionet’s global network, where modernist icons meet the digital age, and let a century-old salon inspire your next bid.

)

)