Amble around the corridors of Farley House, the East Sussex home of the inimitable Lee Miller, a multi-hyphenate long before the term had been coined; Vogue model, muse to Man Ray, portrait photographer and photojournalist through the atrocities of World War II and you will find a note: ‘Lee who caught me in her cup of gold, The Road is Wider than it is Long. Roland.’ Dedicated to Miller from her second husband, Roland Penrose, (m.1947) a British surrealist artist and poet who had met Miller in France, with a mutual friend, Pablo Picasso, the short note, arguably, enacts the courageous and groundbreaking life of Miller better than any of the many later studies into her life by historical researchers.

)

Lee Miller with her army peers, 1943 (second from right). Photo: Wikimedia Commons © U.S. Army Official Photograph

Living through the early to mid 20th Century, a time of unequivocal change in art, culture, society and female roles driven by the outbreak of the War, Miller’s oeuvre might have been an incisive record into the historical moment she was living, but her approach to life represents a modern meaning of feminism: seeking truths, supporting fellow female voices, and living a life of passion and resilience on her own terms- in the case of Miller much to the chagrin of those around her, conditioned by the societal lens of that time.

Her lasting legacy as a wartime journalist (she was one of the very first photographers through the gates of Dachau in the liberation) to protect the stories of the victims of the conflict and telegraph the dark side of history back to the offices of British Vogue (who published the images), as well as her impact as a pioneering woman, has been celebrated in the recently released film, ‘Lee,’ starring, directed and produced by Kate Winslet in association with Miller’s surviving son, Anthony Penrose.

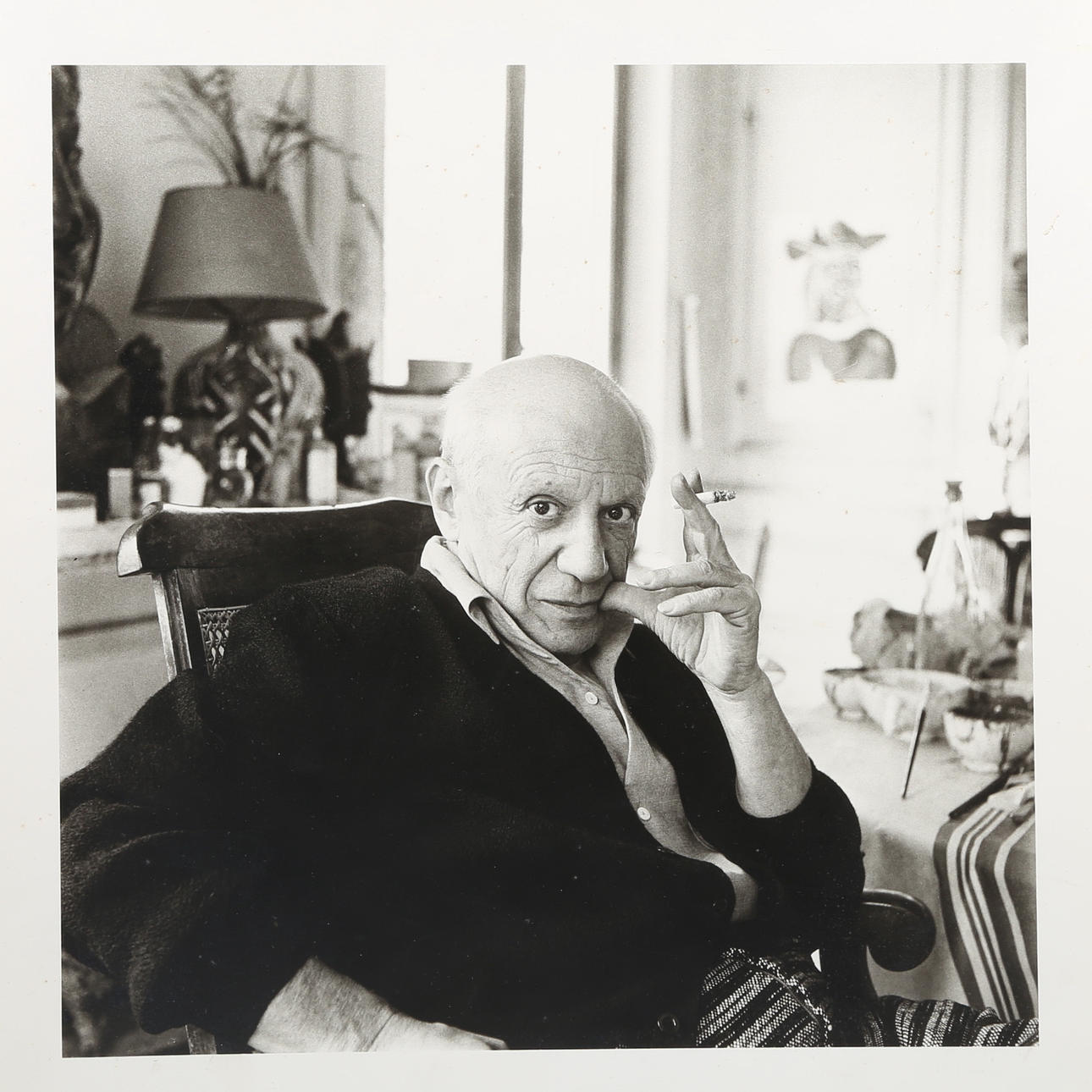

However, it is perhaps the earlier period of her life, as part of the Parisian based avant-garde artist illuminati of the early 1920’s, who were developing the creative ideas behind the Surrealist movement, which is less understood today. Initially Miller moved to Paris to work as ‘student’, later as muse and lover to surrealist artist Man Ray, also developing a good friendship with Pablo Picasso, whom she regularly photographed.

Visit Farley House with Auctionet Academy, and walk in the footsteps of Lee Miller and Roland Penrose. Completely free – our treat!

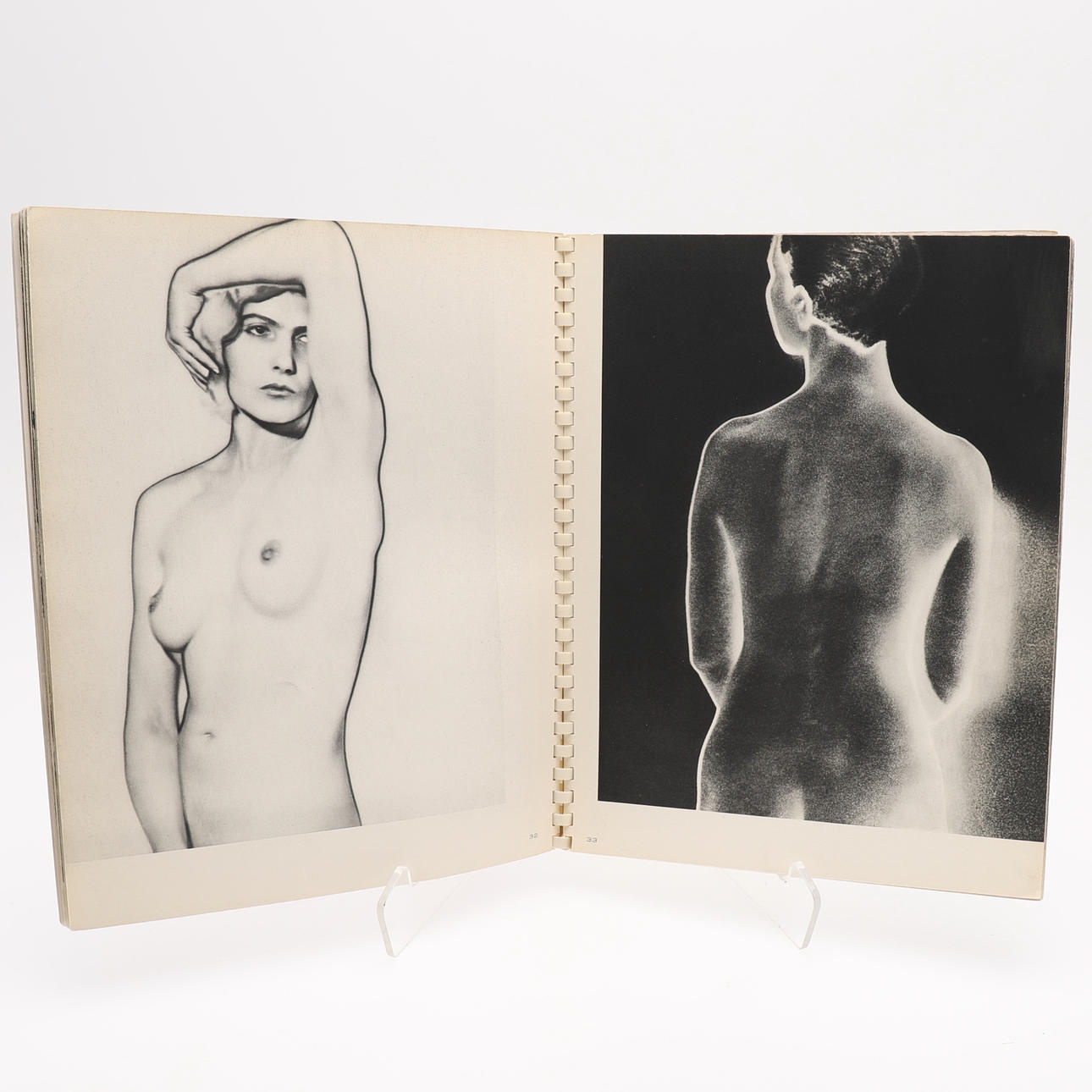

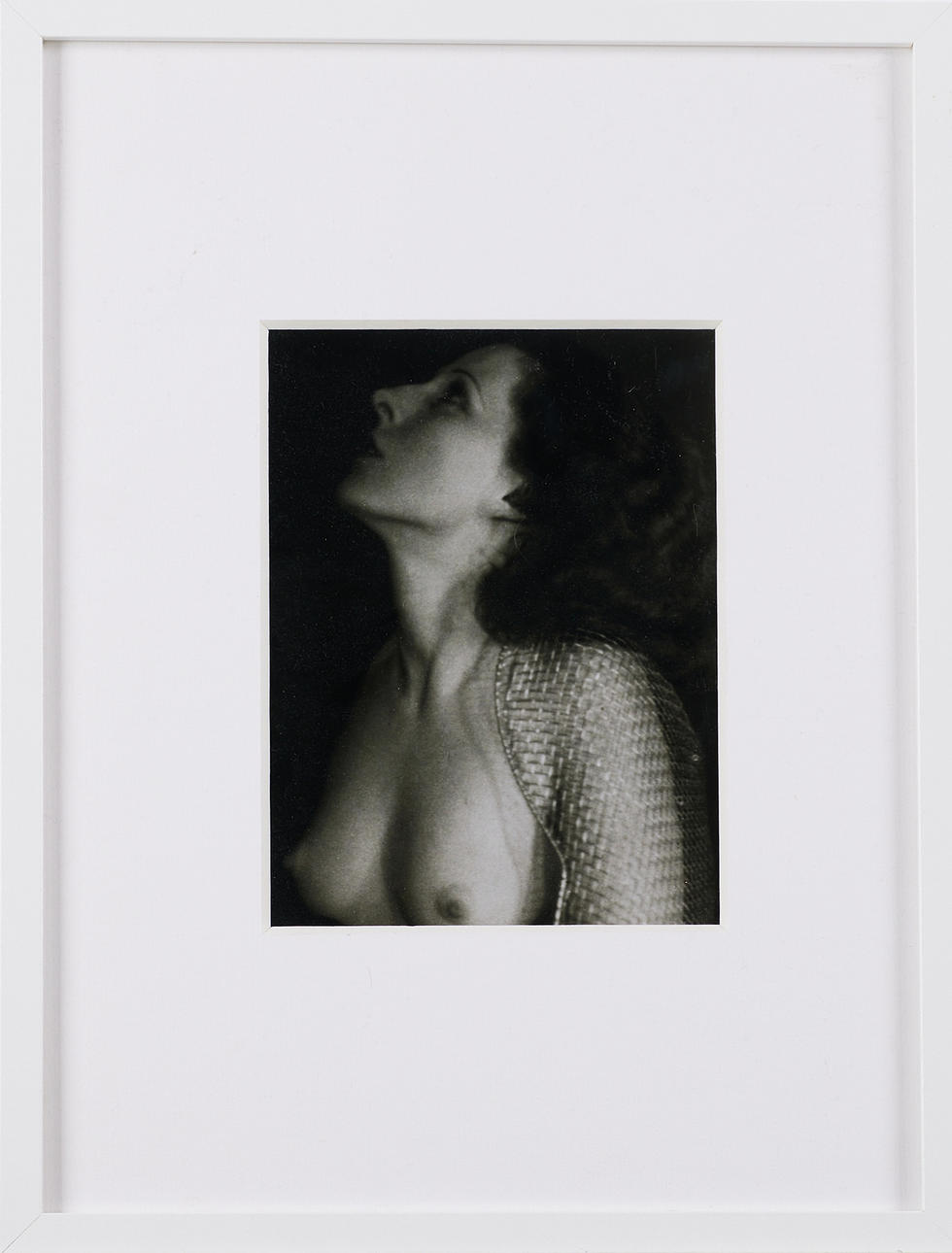

In postmodern times where the notion of ‘muse’ – a term dating back to the Ancient Greek, ‘Mousai’ – reflecting woman as a subordinate beauty, attraction and inspiration to be subsumed through the male gaze, has derogatory connotations, Miller’s relationship to Man Ray transcended that traditional subject-observer dynamic; Miller was largely responsible for progressing surrealist ideas and the direction of Man Ray’s artwork itself. One of the most innovative photographic techniques she created with Man Ray was Solarisation, which is still used today, and became Ray’s trademark: whilst Solarisation wasn’t altogether a new visual signature, Miller stumbled upon its effects when an accident forced her to turn on the darkroom lights whilst developing a photograph. The dystopian dream like visual effects of Solarisation can be described as ‘positive and negative occurring simultaneously,’ and can best be witnessed in Solarised Portrait of Lee Miller by Man Ray 1929, Solarised Portrait of Merit Oppenheim by Miller, 1932, and Solarised Portrait of Lilian Harvey, 1932.

It was also Miller who was influential in creating Man Ray’s acclaimed ‘Electricite’ series’ of rayographs and the black and white film footage used at the Bal Blanc ball in 1930.

Miller later opened her own photographic studio in Paris, taking on much of Man Ray’s photographic clientele, so he could focus on painting, and during this fruitful period she advanced much of the surreal photography style through her own female lens, elevating the everyday in her images, as well as liberating and empowering women .

One could argue that Miller embodied surrealist principles before she even moved to Paris and became part of the movement’s creative kismet. She had the determination to pursue her life free of societal constraints, a core tenet of the Surrealists, who wanted to create a new world order not based on religion or logic but mystery and divine consciousness.

Furthermore, Lee Miller’s influence on Man Ray’s vision extended well beyond their creative union in Paris. She left him in 1932 to return to New York: it was in his despair that he created some of his most acclaimed pieces, including Object to Be Destroyed, the metronome featuring the ticking eye, which was in fact Miller’s eye. The idea was based around exorcising lost love through smashing the ticking eye swinging back and forth. Other profound works Man Ray created in response to the end of his relationship with Miller include his Lip series of paintings and objet d’art based on Miller’s lips: the famous The Lips took Man Ray two years of work to get right with the deep red colour symbolising emancipation. The Lovers is another creation from this traumatic period, in which he addressed grief by adding to the image every day for several years to help him through his loss.

Other Surrealist artists impacted by Miller’s ice-blonde, rebellious form of beauty include Jean Cocteau who cast her in his famed short film, ‘The Blood of a Poet,’ 1932, where she plays a marble statue coming to life. Ironically, this could be an analogy for her life as Cocteau casts her not as a beautiful stagnant object but a disobedient statue that comes to life and refuses to conform.

One of Miller’s most pervading friendships, though, was with Pablo Picasso – it was on holiday in Antibes, France in 1937 that Picasso introduced her to Roland Penrose – in 2015 the Scottish National Portrait Gallery even celebrated the relationship between the trio in an exclusive exhibition. It is largely Picasso who is credited with ‘finding’ Miller’s talent beyond muse and model to portrait photographer in her own right. Whilst less is known of the relationship between Picasso and Miller than of her rapport with Man Ray, Lee even described herself at the time as a ‘Picasso Widow,’ attempting to separate her own photographic career from the association of his friendship: Picasso allowed her to photograph him over 1000 times in 40 years, both at work and leisure, which was rare since the artist was well aware of the value of his own image.

Whilst Miller’s life on reflection has largely been categorised into chapters, where her surrealist work is always considered in the context of her time in Paris with Man Ray, Surrealism actually pervaded throughout her life: she moved to Britain with Roland Penrose in the late 30’s as World War II was imminent, furthering the movement in the UK, and immersing herself with fellow surrealist thinkers. Post World War II and her experiences witnessing the atrocities of those tortured in the Dachau camp, which left her permanently traumatised in later life, Miller actually reunited with both Picasso and Man Ray, finding friendship again until her death in 1977.

Subscribe to search word Lee Miller, and we'll notify you when her work is up for auction.

She once said ‘Everywhere I went things seemed to happen;’ it seems significant as we are entering a new post truth age of image that her story is being re-told, in the context of a woman with formidable agency, who constructed her own life narrative which can resonate with female artists today.

)

)

)