It’s practically a cliché, the notion of the creative duo. But clearly, there's an allure, and perhaps even a formula for success, in the idea of a romantic relationship that also serves as a creative partnership. In the art world, there seems to be no shortage of electric relationships that have sparked both fiery feelings and trailblazing art.

Frida and Diego: A Love Story In Bold Strokes

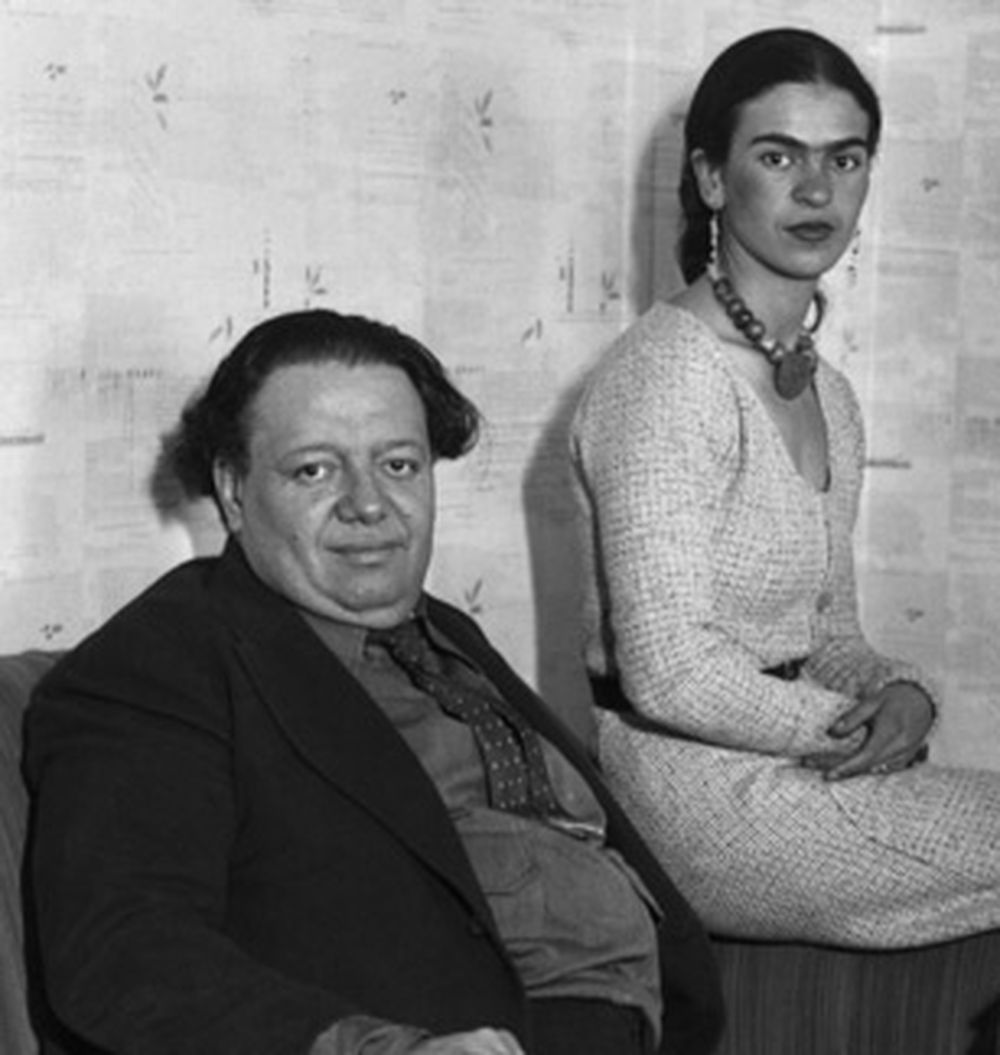

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Credits: Wikimedia Commmons.

The tumultuous relationship between Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera is, in many ways, the archetype of how we view an artistic relationship: infidelity, passion, and a furious creative force. In many respects, it also reflects the typical distribution of fame between creative heterosexual couples: during her lifetime, Frida Kahlo was primarily known as Diego Rivera's wife. It wasn’t until the late 1970s that her art began to be highlighted by feminist scholars, before becoming one of the world’s most significant and celebrated bodies of work.

Creating In Chaos – The Story of Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock

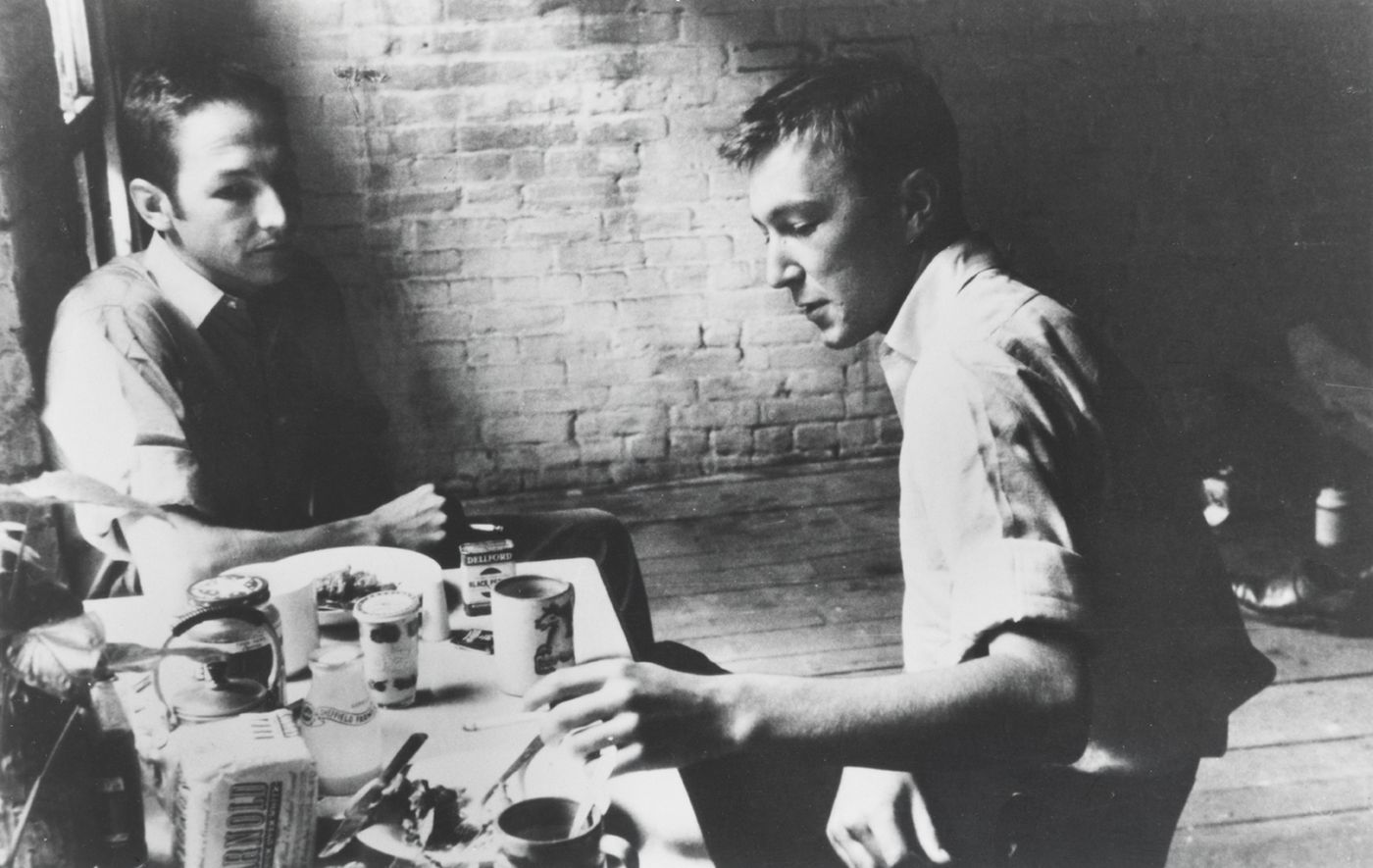

Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock.

Lee Krasner also lived in the shadow of her famous husband, Jackson Pollock, during their lifetime, but in recent years, Krasner's work has gained more attention. Although earlier accounts suggested that Krasner gave up her own art when she met Pollock, later exhibitions have shown that she continued to create throughout their relationship, even after Pollock’s addiction to alcohol made him stop painting. She constantly experimented with new styles—often reworking and, in many cases, destroying her earlier works.

Two Minds, One Canvas: Gilbert, George and a Life in Tandem

Gilbert and George. Credits: Wikimedia Commons.

One of the art world’s most iconic duos, Gilbert & George, also shares a love story straight out of a film. They met at Saint Martin’s School of Art and claim that love blossomed instantly, largely because George was the only one who understood Gilbert’s broken English. Since then, they have become famous for their vibrant art, which they describe as “art for all.” Take a walk down London’s East End and, sooner or later, you’ll see the pair walking side by side in brown-grey tweed suits.

Abstract Emotions: The Romantic and Artistic Entanglements of Rauschenberg, Twombly, and Johns

Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Credits: Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

Overall, it seems fair to say that artistic alliances are often associated with a certain degree of darkness.

The story goes that in the early 1950s, the young art student Cy Twombly ran into the pitch-black waters of a lake outside the fabled Black Mountain College in North Carolina. The young artist Robert Rauschenberg had attempted to take his own life but was rescued from the water by his then-lover. Shortly afterwards, Twombly won a grant from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, enabling him to travel through Italy and North Africa with Robert Rauschenberg. A few years later, Rauschenberg had found love in another young artist: Jasper Johns. Together, they would go on to change art history. Cy Twombly moved to Rome and got married, but some suggest that his increasingly romantic and sensuous abstract expressionist art may have been inspired by his travels through Rome as a young man with Robert Rauschenberg.

Modernists In Love: How the Aaltos Revolutionized Architecture and Design

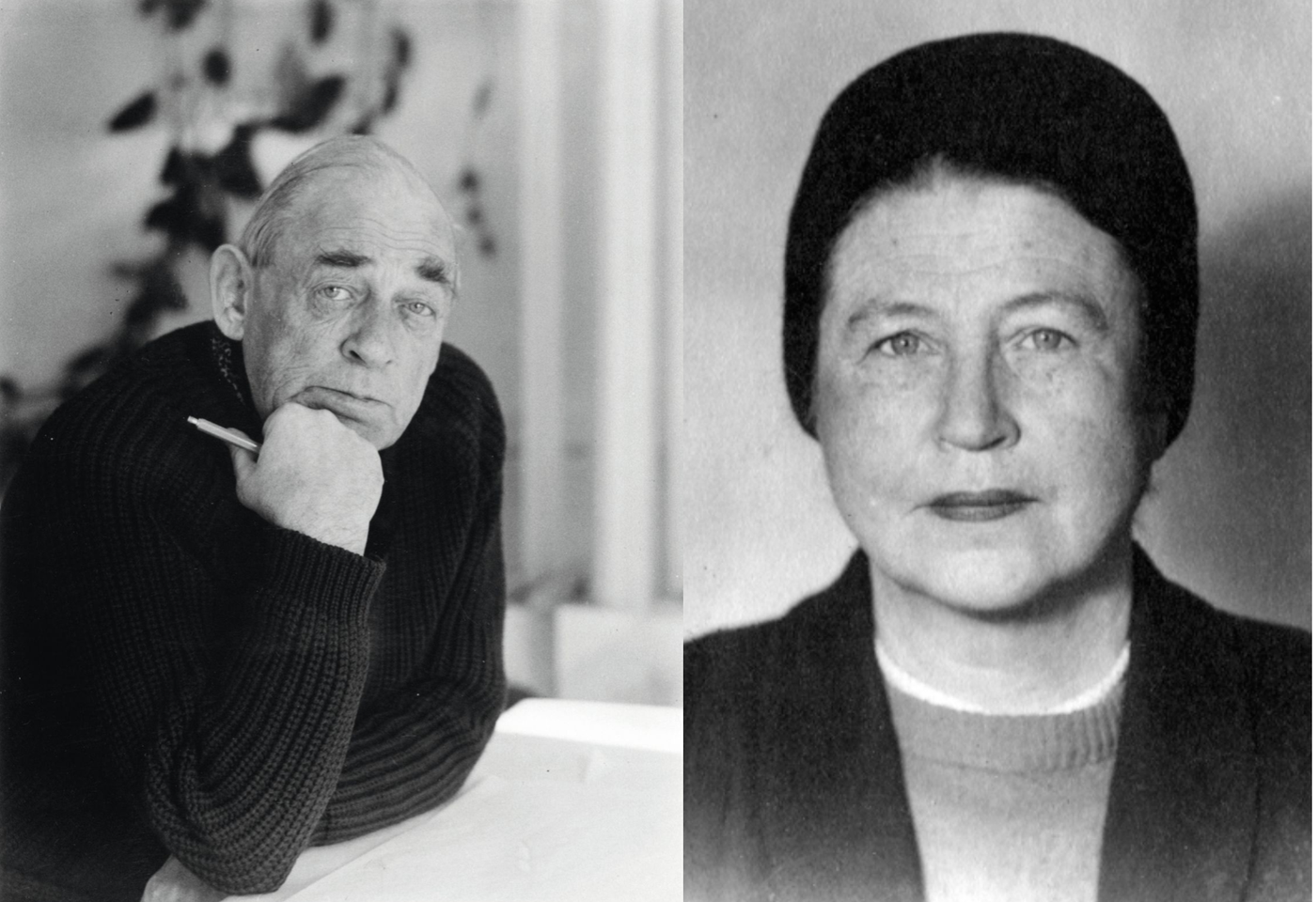

Alvar and Aino Aalto. Credits: Wikimedia Commons.

What about the world of design? Perhaps due to its practical nature—anyone who has tried to assemble furniture with their partner likely understands why—it’s easy to assume painting side by side might be easier than moulding a chair together.

The Aaltos were both architects and met when Alvar hired Aino at his newly opened architectural firm in 1923. The following year, they married and laid the foundation for a design legacy that remains as radical as it is functional. Together, Alvar and Aino Aalto would design numerous classic design pieces. Among the couple’s extensive catalogue are pieces like the Paimio chair, originally designed for a tuberculosis sanatorium in Finland, whose pressed wood and unique shape were intended to ease patients' breathing, and the Savoy vase, whose wavy form has become almost synonymous with Finnish design. During their lifetime, Alvar received most of the attention, but today experts say it’s difficult to distinguish who did what. The couple is now seen as a prime example of collaboration in its purest form: four hands so synchronised they function as one.

Knoll: A Celebration of the Creative Collaboration

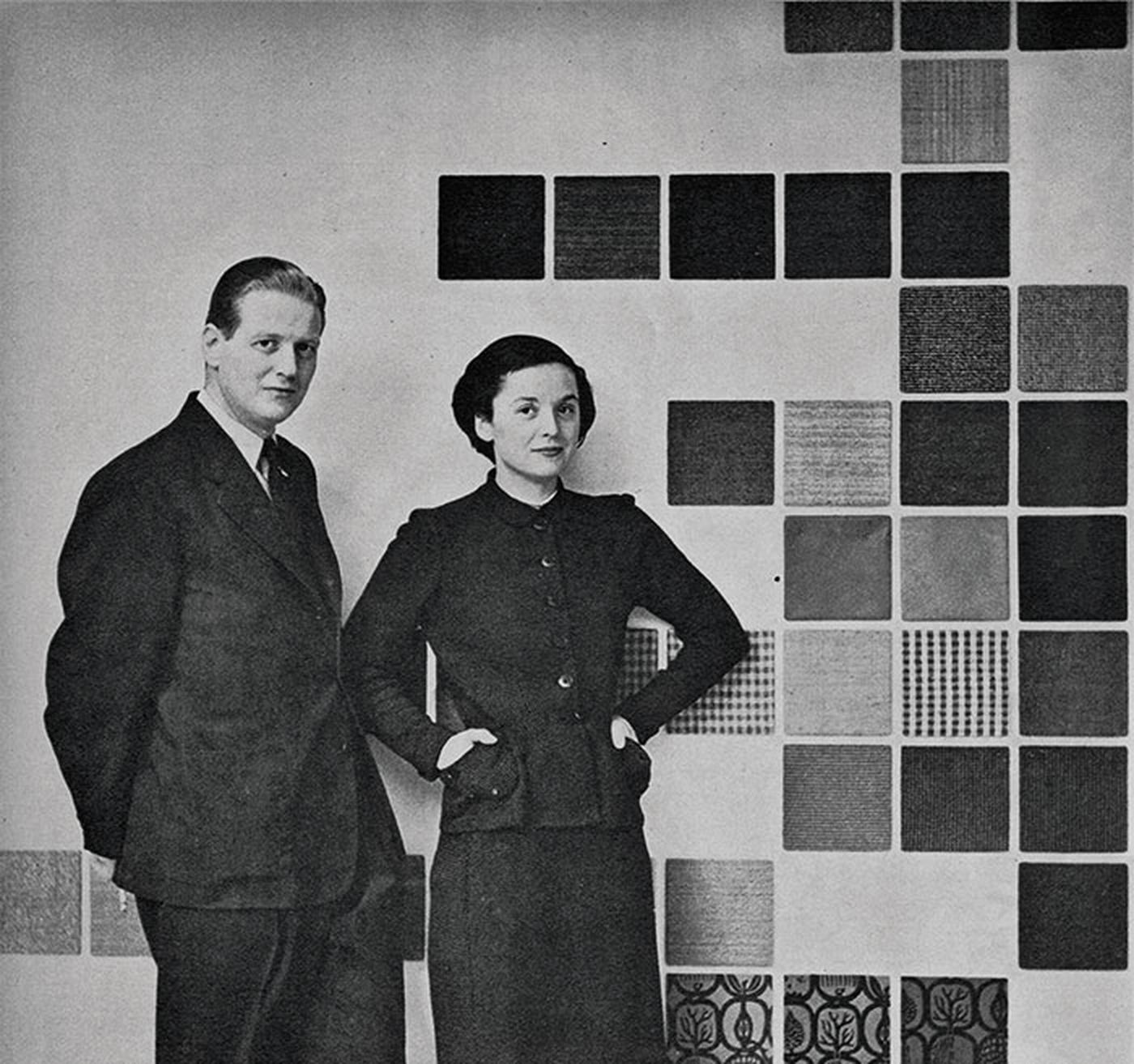

Hans and Florence Knoll. Credits: Wikimedia Commons

The Knoll couple had a clearer division of labour. In the early 1940s, Hans Knoll had founded a furniture company with Danish-American designer Jens Risom. One day, he met a woman who would change both his life and design history. Florence Schust grew up in Michigan, also of German descent. After her parents passed away at a young age, Schust was placed in foster care before her teenage years. A few years later, she began studying at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, where a certain Eliel Saarinen resided. He and his wife Loja practically adopted Schust. She became friends with their son, Eero Saarinen, and continued her studies in London after receiving advice from Alvar Aalto.

In the early 1940s, she worked as an intern under Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, and in 1941 she moved to Chicago to study under Mies van der Rohe. Florence Schust met Hans Knoll’s office in 1943 and married three years later. Florence Knoll transformed a small furniture company into an international design house, with the help of Hans Knoll’s business acumen. She designed pieces herself, but perhaps her greatest talent was her ability to bring out the best in others: she invited friends, acquaintances, and former teachers to design for Knoll, including Eero Saarinen, Marcel Breuer, and Pierre Jeanneret. Among the masterpieces created for Knoll under their leadership are Saarinen’s Tulip Chair, Bertoia’s Diamond Chair, and Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona series.

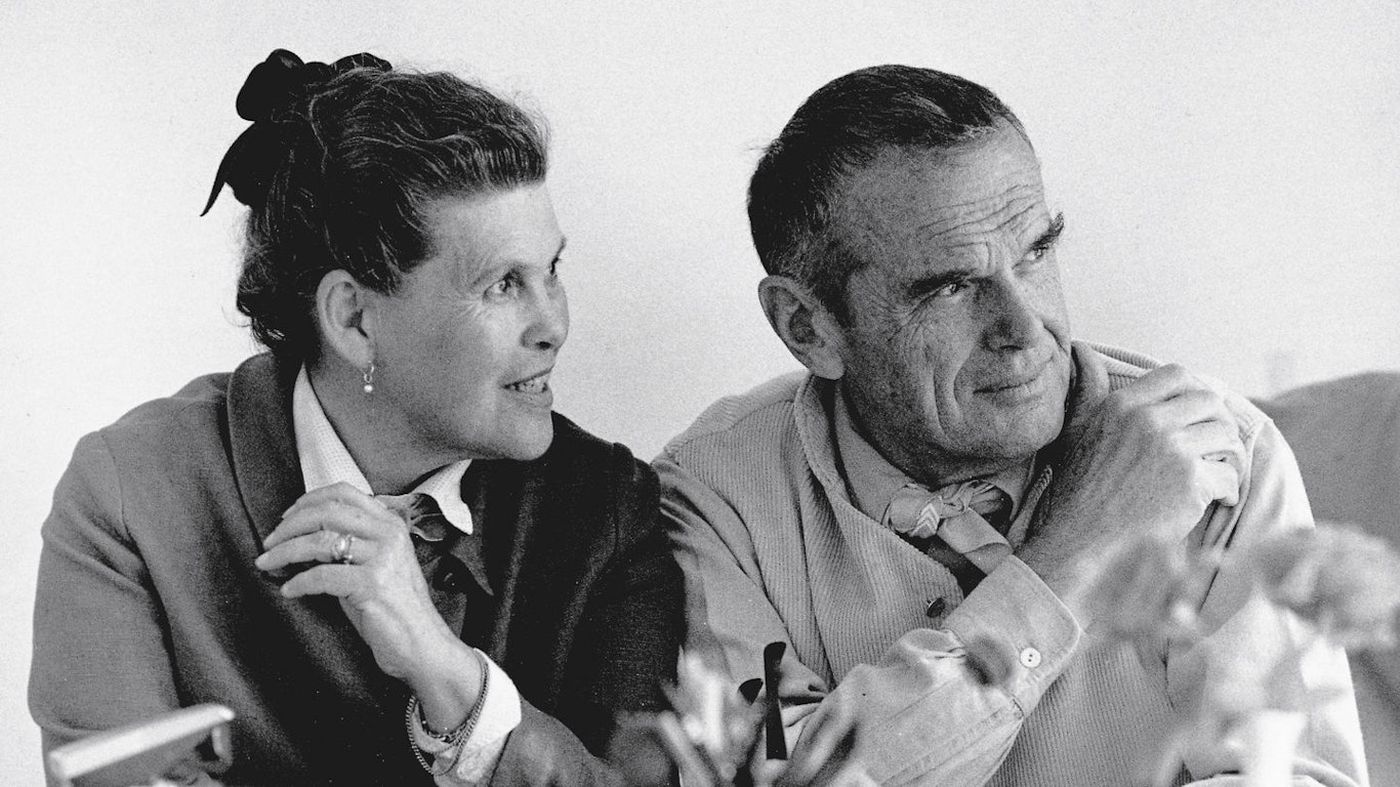

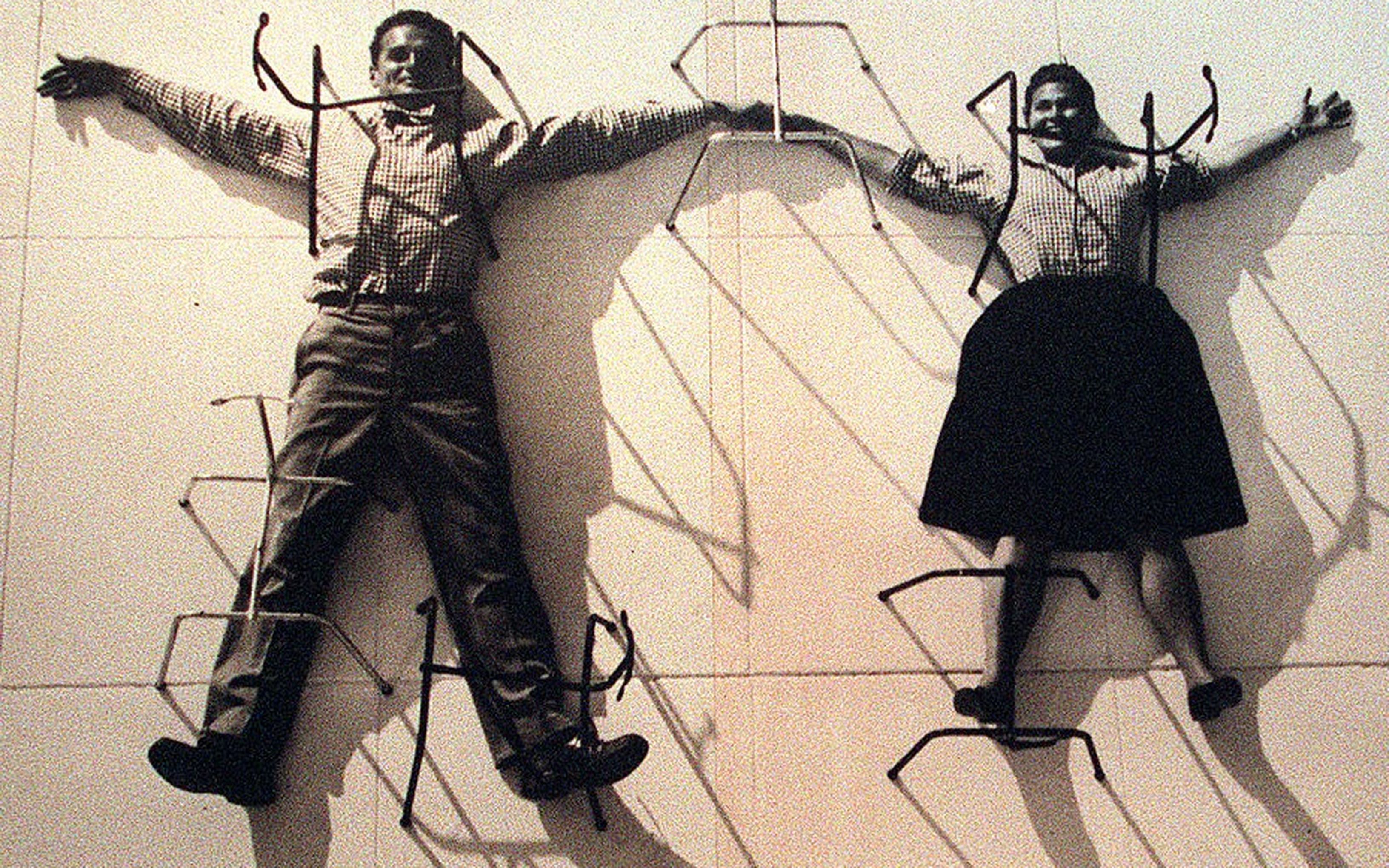

Eames by Design: The Duo that Redefined Mid-Century Modernism

Charles & Ray Eames. Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Around the same time, one of design history’s most iconic alliances was formed. Charles Eames had been forced to leave his studies at Washington University for being a bit too influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright’s radical ideas. Instead, he received a scholarship to Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan through, you guessed it, Eliel Saarinen, whose son would become his best friend. Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen entered a competition organised by MoMA with The Organic Chair; born from an attempt to mould a block of plywood into a chair. With the help of his new acquaintance Ray Gayber, an art student at the same university who assisted with drawings and models, the duo—or trio—won first prize. The competition changed everything. Charles Eames divorced his wife and proposed to Ray Gayber. A month later, they were married. Their honeymoon was a road trip to Los Angeles. Along the way, the couple collected tumbleweed from the roadside, which they later hung from the ceiling of their iconic Eames House. Among the masterpieces the couple would go on to create are the Eames Lounge Chair, Eames Plastic Chair, and Wire Chair.

Then there are the couples who meet through design. When art critic Aline Louchheim travelled to Detroit for The New York Times, it was to interview Eero Saarinen about the construction of the General Motors Technical Center in Michigan. In later interviews, she recounted how she first fell for the grand building – and then for the architect himself.

The following year, Louchheim and Saarinen were married. The couple had one child together: Eames Saarinen.

Find items from our archive

)